Nous reproduisons un article (en anglais) publié par le Weekly Worker du 12 avril 2012. Sous le titre Momentum builds behind Frances third man (traduit par Un mouvement se contruit autour de la candidature Mélencon) Jean-Michel Edwin appelle à un vote critique pour le candidat du Front de gauche.

Nous reproduisons un article (en anglais) publié par le Weekly Worker du 12 avril 2012. Sous le titre Momentum builds behind Frances third man (traduit par Un mouvement se contruit autour de la candidature Mélencon) Jean-Michel Edwin appelle à un vote critique pour le candidat du Front de gauche.

Campaigning for France’s two-round presidential election is hotting up. The first ballot takes place on April 22, when all but the top two candidates will be eliminated, and the second round will be held on May 6. The monarchical president – either rightwing incumbent Nicolas Sarkozy or one of his opponents – will form a provisional government, and will hope to gain a majority of deputies in the French national assembly when the legislative elections are held on June 10 and 17.

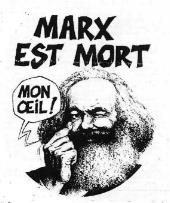

Sarkozy and the Parti Socialiste candidate, François Hollande, are running far ahead of their opponents and look set to qualify for the second round, but the Front de Gauche (FG) candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon, in alliance with the Parti Communiste Français, has unexpectedly gained support and now stands at 15% in the polls. He has promised his enthusiastic working class supporters that he will qualify for the second round: “We will do it!”

According to the media, Mélenchon is the “hard-left” candidate who calls for a “citizens’ revolution” (révolution citoyenne). Last week he raised the demand that Sarkozy “account for the misery and ignorance he has spread during his five years in office”. He was speaking at a rally at the Place du Capitole in Toulouse in front of 70,000 red-flag-waving supporters – only the latest in a series of mass rallies, where tens of thousands workers have come to hear him across the country. The climax of his campaign should be a monster rally in Paris three days before the election, where 100,000 are expected to gather from all over France. “This is not an ordinary campaign,” Mélenchon says, “but the first stage of a revolution: you cannot stop us! We can’t lose because it’s not only an election, but the révolution citoyenne on the march!”

Early campaigning

The classic right-left stand-off between the conservative Union pour un Mouvement Populaire, plus liberal allies, and the Parti Socialiste began to take shape when the PS organised primary elections open to every French voter in October 2011. For the first time these primaries were opened up to candidates of other leftwing parties, but only the bourgeois Parti Radical de Gauche availed itself of the opportunity to join in – the FG, PCF and far-left organisations kept their distance.

The PS primaries need to be mentioned, as they attracted more than 2.5 million voters – far more than the PS membership. Amongst the six candidates in the first round, François Hollande finished ahead of Martine Aubry and the former won the second round. But the third candidate was PS leftwinger Arnaud Montebourg, who picked up an unexpected 17%.

In a press release issued on December 9 Mélenchon congratulated Hollande, but put particular emphasis on the Montebourg result: “… I note especially the spectacular breakthrough of Arnaud Montebourg and his ideas of rupture, which he raises in terms often identical to those of the Front de Gauche”.

As campaigning began to get underway in January, Hollande was ahead in the polls – Sarkozy waited until February 15 to officially announce his own candidacy. Behind them were Marine Le Pen of the far-right Front National and the liberal François Bayrou, both with over 10% of voting intentions. At that time Mélenchon was languishing in fifth place – although even his 9% support contrasted favourably to the actual votes won by his most important current ally, the PCF, in the previous two presidential elections (just over 3% in 2002, falling to below 2% in 2007). The far left was, and is, doing even worse, with both the New Anti-capitalist Party (NPA) and the Trotskyist Lutte Ouvrière barely showing at only 0.5% each.

In the 2007 presidential election NPA candidate Olivier Besancenot received 4.08% of the vote (a little down on 2002, when he stood for the Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire) and the perennial Lutte Ouvrière candidate, Arlette Laguillier, won 1.33% (a big drop from the 5.72% she had registered in 2002). Overall the far left’s electoral support seems to have diminished from around 10% five years ago to about 1% today. The fact that Besancenot stood down in favour of rank-and-file worker Philippe Poutou for the NPA, while comrade Laguillier retired and newcomer Nathalie Arthaud was selected for LO, does not explain this backward movement.

There is no doubt that the left-moving Mélenchon will gather the main part of the traditional far-left vote for the PG.

Sad tale of NPA

Readers will remember that the NPA (Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste) was formed in February 2009 on the initiative of the Fourth Internationalist LCR, whose comrades made up the majority of the NPA’s active membership. The new party gained rapid support and later that year was claiming 9,123 signed-up members. Comrade Besancenot, who held out the “possibility of a new May 1968”, was dubbed the “de facto leader of the left” by one of Sarkozy’s ministers.

But Besancenot failed to go beyond the radical rhetoric. As millions of French workers went on strike against the Sarkozy government’s anti-working class attacks, in one of its first acts the NPA leadership joined forces with Mélenchon’s Parti de Gauche and the PCF in signing a statement “supporting the CGT and the other seven main trade union federations in putting ‘the maximum pressure’ on the Sarkozy government to ‘oblige it to enter discussions’ with the unions”. As we wrote at the time, the NPA backed “a cosy consensus with the government” when the working class needed “a clear political lead and a programme to break with the token protests of the union bureaucrats” (‘Everything to play for’ Weekly Worker February 12 2009).

At the same time Mélenchon, an ex-PS leader who had been a minister in Lionel Jospin’s 1997 government, was launching the broad Left Front (Front de Gauche) around his newly formed Left Party. Mélenchon called on the NPA to join an FG common list in the 2009 European elections together with the PCF. This proposal was welcomed by the NPA’s minority led by ex-LCR leader Christian Picquet, but the majority, including comrade Besancenot and veteran LCR leaders Alain Krivine and Daniel Bensaïd, put a condition on such an alliance: they would only join the Left Front if a long-term agreement was reached not to enter into any alliance with the Socialist Party in future elections, beginning with the regional elections in 2010.

Together with other Marxist members of the new NPA I considered at the time that instead of supporting a Mélenchon-PCF list in the European elections the NPA should formulate a “minimum revolutionary platform” for working class unity on a European scale, call on Lutte Ouvrière and others to join a list based on such a platform, and use the election to build the NPA profile and structures. Most probably this perspective was an optimistic one, as it went far beyond the NPA’s dynamics and capacity.

Instead of that, the NPA leadership took a ‘centrist’ position: while refusing Mélenchon’s proposal (Picquet and his supporters accepted them, splitting from the NPA and joining the FG), the NPA did not adopt a clear stand. It delayed several months before launching its own European list and platform, having engaged in seemingly endless discussions with the PCF, Mélenchon and other leftwing currents to try to reach an agreement. But these discussions took place behind closed doors, with little publicity: a kind of leftwing ‘secret diplomacy’, when an open and public debate would have been much more acceptable and productive.

This turned out to be even worst than an electoral agreement would have been: as the European elections have no practical consequences in reality (since the European ‘parliament’ has no real power), an electoral united front with the FG – for instance, a common list, with the different components standing on their own separate platforms – would have been far better. As it was, the NPA seemed paralysed until June 2009, and this caused more and more divisions within its ranks. The interminable discussions even gave rise to the idea of a possible “common programme of the left” uniting reformists and revolutionaries around a common platform: the same opportunist illusion which had destroyed the old PCF hegemony in the working class and prepared the way for the success of Mitterrand in the 1970s.

Some leaders of the NPA majority tendency, who were at the time amongst those most opposed to any alliance with Mélenchon, are today part of the mass desertion of the NPA for the Front de Gauche. The ex-NPA “Anti-capitalist-Left” is now pleading (rather unsuccessfully) for a good share of candidates for the FG’s legislative election campaign in June. One must remember that Mélenchon’s 2009 call to the NPA came before he was able to rally the PCF behind him: he was then asking for the support of the most successful electoral representative of workers, Olivier Besancenot.

In the end the Front de Gauche got 6.05% in the Euro elections and the NPA 4.88% . As soon as they were over, the NPA leadership entered into fresh discussions with the FG and others on the regional elections, which were to take place in March 2010. The talks centred again on the “PS question” and the supposed necessity of a “common programme”. The radical NPA had become mainly concerned with elections. In the event – one year after the NPA had been launched, having built on the previous electoral successes of comrade Besancenot – it went into the regional elections deeply split within its own ranks. While the FG more or less maintained its share with 5.84%, the separate lists of the far left (NPA and LO) could only muster 3.4% between them.

Radicalised working class

Since the presidential election of 1995, the tendency has been for the revolutionary left (the LCR, then NPA, and LO) to increase its share of the vote at the expense of the PCF. But most of all 1995 had marked a turning point in the mass movement – the November-December general strike was the largest since May 1968.

In 1995, the newly elected president, Jacques Chirac, and his prime minister, Alain Juppé, launched a massive programme of welfare cuts. Students and later workers went into action, with the major trade unions striking against a pay freeze and the ‘Juppé plan’. The strikes paralysed the whole country and Juppé was forced to tone down parts of his planned ‘reforms’. There followed major resistance to both the March-June 2003 assault on pensions, with millions on strike and on the streets in 2006, 2009 and 2010.

None of these movements obtained any important concessions from the ruling class – the right was in office for the whole of this time except for 1997-2002, when Lionel Jospin formed a PS government under Chirac’s rightwing presidency. The only real victory in this whole period came when students and young workers rebelled in April-May 2006 against Juppé’s CPE (first employment contracts).

As for elections, the increased support for the far left has been accompanied by reduced turnouts – this growing abstentionism has produced easy victories for the right. The class has proved its combativity and capacity to mobilise when it comes to strikes, but has obtained little to show for it and, most importantly, has failed to leave its mark on the political stage. But does the sudden upsurge in support for Mélenchon represent a departure?

According to Lutte Ouvrière, class-consciousness is low and the working class mood is one of disarray and despair. “Nothing serious has happened in this country,” LO leaders say, “since the 1871 Paris Commune and we have to be patient: it may take a century or more to have another Commune.” Hence the LO candidate Nathalie Arthaud’s logical conclusion: “To get rid of Sarkozy, as Hollande, Mélenchon and Poutou say, doesn’t mean anything, because Hollande would be no better than Sarkozy – he defends the bourgeoisie as well.”

There is more than a hint in all this of LO excusing in advance the poor showing of its own presidential candidate. In fact the powerful class momentum in favour of Mélenchon represents a step forward despite his reformist programme. Our class wants to call a halt to the massive social destruction and injustice Sarkozy has promoted and implemented in office. The reason why Hollande might well be elected, on a platform that is, of course, much more timid than Mélenchon’s, is that he promises to stop the social tsunami against the working class via a ‘softer’ austerity programme.

But even this is apparently unacceptable to the ruling class and finance capital, whose representatives are already warning that France will suffer devastating attacks via the monetary markets if Hollande is elected. He will come under intense pressure to become what Mélenchon calls “Hollandreou” (after the name of the former socialist Greek prime minister). Either France’s workers will resist or they will face the Greek treatment. That is why the most militant sections of the working class are rallying behind Mélenchon.

And that is why many Marxists in France are now calling for a vote for Mélenchon, combined (probably) with a vote for Hollande in the second round of the presidential election. Even some comrades who are still involved in the NPA, trying to salvage something from the project, and who are calling out of loyalty for a vote for the NPA’s Philippe Poutou, are engaging in the movement and rallies in support of the FG candidate. As one such comrade put it to me, “We cannot stand apart like the sectarian left”.

The call is: build the movement; critical support to Mélenchon.